Incarcerated women & trauma

“Data concerning the health and mental health status of incarcerated women reveal that at least 60% of women in state prison reported a history of physical or sexual abuse (BJS, 1999)” as quoted by Beth Richie (2001) in Challenges Incarcerated Women Face.

There is a heart-pounding disturbance here. Anger. Anger at the system that does not have mechanisms, programs, laws, and protection for the mis-management of justice. Anger at the rent social fabric of an unprincipled America, at that male ilk which is responsible for many of these crimes... Two thirds of the women in prison are of color.

Learning about the uphill struggle of incarcerated women reminds one of the inequality in poverty. Economists have used the “girls in secondary education” or women in “higher education enrollment” statistics to gauge how developed a country is, or how rapidly it will change. Investing in women education saves two generations: the woman who is going through the education system now + investment return in her children when she becomes a mother. Similarly, poverty and incarceration affect two generations: the woman serving jail-time suffers; the under- or unemployed woman faces poverty… and at the same time their neglected, un-cared for children also suffer.

Cherise Charleswell documents how gentrification is a Feminist issue at the intersections of race, gender, class, and inequality. She gives voice to the feminisation of poverty, a dearth of wage growth, and how both of these trends increase the marginalization of women into less equity retaining, un-safe neighborhoods. Poverty statistics get worse: one in eight children in the US are hungry (poor to the point of malnurishment). The great majority of single parents in America are single-moms raising a family. Coupled with 0.75 of a man’s wage (or less), these women face one of the hardest battles of providing their children with the same opportunities. A few organizations and programs mitigate this: taking special care of the children of mothers in custody, busing them to reunite families, give hope, and share love.

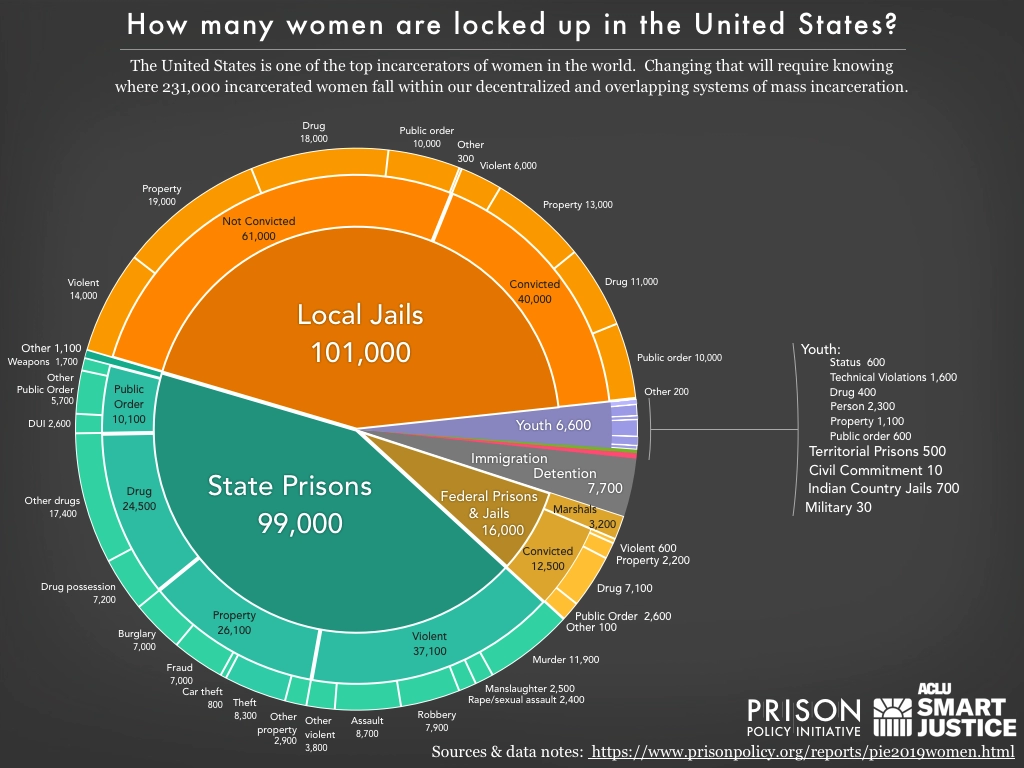

https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2019women.html

Riche states the rate of women being incarcerated has increased from 1998, with more than 1.2 million children being affected. That is roughly 2% of all of the children in the United States. About 38% of the charges are related to substance abuse. Very few crimes are related to violence. Prior arrest history was the greatest predictor of post-prison recidivism. Richie finds seven themes that answer: what are the needs of women returning to their communities from jail?

1. Treatment for substance abuse problems

2. Health Care

3. Mental Health

4. Violence Prevention & Post-traumatic stress disorder

5. Educational and Employment Services

6. Safe, Secure, and Affordable Housing

7. Child Advocacy and Family Reunification

One of the incarcerated women that Richie interviewed said, ‘when we come home it is like we serve time again.’ This demands a new incarcerated-woman calculus and re-settlement objectives. Should women, especially women with children, go back to the same communities that landed them in jail – certainly not – when they say ‘No, I do not want to go back!’ However, even when incarcerated women do say they wish to return ‘home,’ they face obstacles.

The broader social and institutional analysis concludes that (1) multiple demands: employment, drug screening, finding a place to live… all must be addressed at the same time, (2) the dis-connection from communities, homes, and institutional stigma, and (3) solutions for the woman (and her children) that are gender-specific and culture-specific are all up-hill battles each returning-from-prison woman faces.

Comprehensive ‘wrap-around services’ for some women may be to leave their communities and begin without the burden of reintegration and negative stigma. The reverse is probably less true: programs and services tied to an incarcerated woman’s original community are less helpful. Asking what the woman wants verses where the woman believes she will be able to forge a better future – allows the practitioner to help counsel.

Creating cultural and gender sensitive comfort may be done on a case basis: focusing on the interests, hobbies, goals, and desires of the woman (and her family unit) – for which ever neighborhood she chooses to live in. A community development approach helps galvanize social change strategies through higher quality work, awareness, and policy changes.

Structural awareness for what factors influence the decisions of battered- or substance abuse women raises Self-consciousness. Having a mentor that is seen as “like them,” as a neighbor, or part of a program staff is key, says Richie. In conclusion she observes, womens’ self-sufficiency and safety needs if observed in low-income communities can prevent incarceration in the first place.

Weinstein, Wolin, and Rose put out a trauma-informed community building report in 2014. Change for incarcerated women begins with a multifaceted support structure. Trauma is a natural human response to the complex circumstances that these women (and men) in poor neighborhoods battle through every day. Violence, crime, poverty, isolation, and poor education are trauma causing situations that surround housing and community development. Weinstein et. al. declare more than 70% of African Americans born in poor neighborhoods will live in these neighborhoods for most of their life. Why do they become so disenfranchised?

The level of trauma disunites. It breaks down trust in the system and others. There is a lack of stability, reliability, hope for the future, empowerment, ownership, coupled with high levels of personal needs. “It is now widely accepted that community building efforts in low-income and public housing neighborhoods seek to counteract the deterioration of social structures and weakened formal and informal institutions that support the life of a community,” the report quotes Wilson 1987 from The Truly Disadvantaged.

Trauma-Informed-Community-Building (TICB) de-escalates stress and chaos on a bureaucratic and personal level. It fosters resiliency by recognizing trauma and combating it, and strengthening social connections. TICB consciousness is the foundation for policy change; it generates stronger potential for long term communal and individual change. This breaks the vicious cycle of poverty and incarceration. TICB helps each concentric circle beginning with: the individual, her interpersonal relationships, the community, and finally outward to the systems and policy that governs.

TICB leads into the discussion of how more women should be involved in city planning (and provides on dimension of answers). In designing neighborhoods, resource facilities, education centers, and crafting the policy in light of Richie’s article regarding incarcerated women, committees headed by women, and at least advised by those who are well aware of the set of 7 comprehensive problems faced by incarcerated women, would provide momentum for institutional change. The lack of space, security, female housing, female transport may be addressed in the planning phases.

Jon Davis’ 2014 article describes re-purposing jails into amenities for public or private usage. Because of the nature of their design, prisons tend to have a short life, deteriorate structurally, and are difficult to maintain: heavy iron bars, concrete walls, piping, individual toilets, cramped rooms, fencing and barbed wire. Urbana, IL and Fairfax, Virginia are two prison sites that have made plans to re-purpose the jails into apartments and artist living communities. The Yonker’s City Jail was also converted by Daniel Wolf and Maya Lin into an art studio and museum.

Finally, and in conclusion, the most powerful mobilizing factor begins before prison release. Many of the interviewed women commented on their illiteracy levels, their dis-interest in their school systems, and lack of job-landing skills. While the two are certainly not linked concretely, this response paper draws attention to Cooks observation that: trauma can affect a person’s self-concept, self-worth, ability, esteem, shame, guilt, etc. In a utopic re-visioning, the correctional systems of the State do just this: adjust for the lack of education, opportunity, environment, and trust.

Less than 40% of women incarcerated were employed before going to jail, counted Richie. This may suggest a number of factors from: women being taken undue advantage of, to opportunity and employment inequity. Because employment is the key to solving a host of complex problems, public housing should facilitate petitions from incarcerated women according to preference of work industry.

If each correctional facility had 4-5 career options to choose, for example, this would afford them advantages in resources and networking. 2-3 facilities work together at one TICB center, built away from the city. Women graduating from one of the 5 career programs have a specific housing township / center they are relocated to, wherein they find a specific niche application of their learned trade-skill. Secondary skills like: nutrition, mental health, exercise, punctuality, attire, add to the core value of learning about ones’ Self and abilities autonomously. The end goal is foremost functionality in the niche TICB -policied, publicly housed, community and township. Next, are the interpersonal skills that lead to increased self-worth and autonomy.

Finally, within that distanced community (away from stigma and burdens of old), tertiary skills are worked upon for continued autonomy. These are not limited to work ethics and expectations, but also encompass technical education from the basics: voice and email, to letter, art, and design compositions, Internet search and research, community college enrollment or GED acquisition (if the individual wants), or simply workshops that discuss the fundamental concepts of economics, accounting, data, marketing, programming, or further development into the niche trade-skill industry.

One example of a trade-skill being implemented in many prisons is soap-making. Tertiary learning and autonomy would go towards understanding chemistry, cleaners, detergents, custodial operations, and procurement of supplies. A better example, and one that should be an option at every prison is horticulture. The open air environment, food provision, and slow nurturing of plants can be therapeutic with financial benefits. Tertiary learning moves towards biology, botany, and longer investments in fruit trees, orchards, and the land itself. If these pathways are guided by TICB organizations in townships that network for progression or diversification into a related job or trade skill… this culminates into a truly integrated, rehabilitated, and empowered citizen.

The State, in such cases, may celebrate. For we have cultivated the means, pathways, and support structure for another ‘good life.’ And that, for the classical philosophers, has ever been our job.

Start writing your post here. You can insert images and videos by clicking on the icons above.